Running LLaVA on iOS With llama.cpp and TinyLlama

I got LLaVA to run on iOS by re-running training using TinyLlama as the base model and llama.cpp for inference. The UI is janky, but I learned a lot getting it to run on device. While there are a lot of projects that run various LLMs on mobile, I think there are only a few that allow images as an input (and I think there weren’t any when I started on this project). Check it out on GitHub. A huge shout out to the author of the llava example in the llama.cpp project, as well as the author of the llama.swiftui (and of course, llama.cpp in general).

Before I started this project, I had very little practical knowledge of how to implement inference, or incorporate a gguf model into a project. I had some idea about the theoretical workings of LLMs, but never did any training or implemented inference directly. Now, I feel pretty confident in my understanding of how Vision enabled LLMs are implemented, and how to run a gguf model on iPhone.

Motivation

LLaVA is a “multi-modal” vision + text large language model architecture that connects images with text for the purposes of answering questions about an image. Originally, I was inspired by the Meta Ray Ban glasses and the AI capabilities. I don’t own them, so I wanted to simulate what could be possible with an AI that has image capabilities built in. Additionally, I felt like all the open source vision + language models all don’t really integrate on mobile, which leads to a really disjointed process. You gotta find the file, and manually upload it on a laptop/desktop. One of the many benefits to mobile apps is that the camera is built right in. You could even tie in things like GPS and other pieces of metadata into the prompt. With these ideas[^1] in mind I started trying to get llava to work on my device.

How I got it working

Copy Pasta till I can’t no more

Initially, I attempted to run llava v1.5 (the 7B model) directly on iOS by copy pasting various functions from the llava example in llama.cpp, and I managed to get it to work! But unfortunately the size of the smallest available model was too large to run on my iPhone 15 pro consistently, and crashed more than half of the time. I spent a little bit of time trying to see if there were any smaller llava models, but couldn’t find any.

Figuring out how to make the model smaller

After my mindless copy pasting failed me, I decided to dig into the details of what exactly I was copying. One thing that I found peculiar about what I was copying that seemed different than other models was that the llava example had two model files. Prior to this project, I had only ever run various text-only LLMs like mistral or llama v2 via llama.cpp which were all distributed with a single file, so I wanted to learn more about what the two files were.

I first watched a video about LLaVA, and then I read the paper (which is fairly approachable). Learning how LLaVA works helped me come up with a strategy on how to make it smaller. In the appendix I’ll go into some of the details, but the gist of it is that LLaVA takes an image, converts it to text embeddings using CLIP, and then samples an LLM that the authors fine tuned to answer questions in a chatbot context.

Since the LLaVA authors provide all the data and training scripts to run training from scratch, I was able to rerun their training scripts using the 1.1B parameter TinyLlama-Chat as the base model instead of Vicuna. I chose TinyLlama mainly because when I ran llama.swift (the iOS example in llama.cpp) on my phone, it actually ran fairly quickly with no crashes, so I knew that it should run on my phone after being trained.

Here’s the model gguf weights, and the projection layer weights. I have not run the llava eval scripts to see how good it actually is, but in my testing, it worked fairly well. Training was a learning experience, with lots of struggles along the way.

Actually running it on iPhone

After I trained the new model, and verified it worked by using the llava example with my trained models as the provided input. But to get llama.cpp and llava specifically to work on my phone took a TON of perseverance. While llama.cpp does provide a Swift Package Manager package, it was missing a lot of really important functions, and the clip related functions were only implemented in the llava examples only. Some of the more frustrating difficulties:

- It’s actually really easy to connect Swift to C code. But any C++ code that uses

std::stringor other STL containers or functions cannot be used directly by Swift. So I had to bridge a bunch of functions via Obj-C++. I wanted to try my hand at SwiftUI, but this project would have been much simpler if I had just done it all in UIKit/Obj-C - I totally accepted needing to copy paste a bunch of LLaVA code from the example llama.cpp. But I found it very weird that a lot of the sampling functions were not a part of the llama.cpp public API! llama.swiftui implements sampling using greedy sampling and does it by hand. I ended up copy/pasting the sampling modules from llama.cpp into my project(removing the grammar sampling logic). It’s possible that it had to with how my project is pulling down the SPM, but it could also be that the SPM may need to be updated.

- The SwiftUI flow of data requirements, about what can/can’t be on the main thread, is just such a pain.

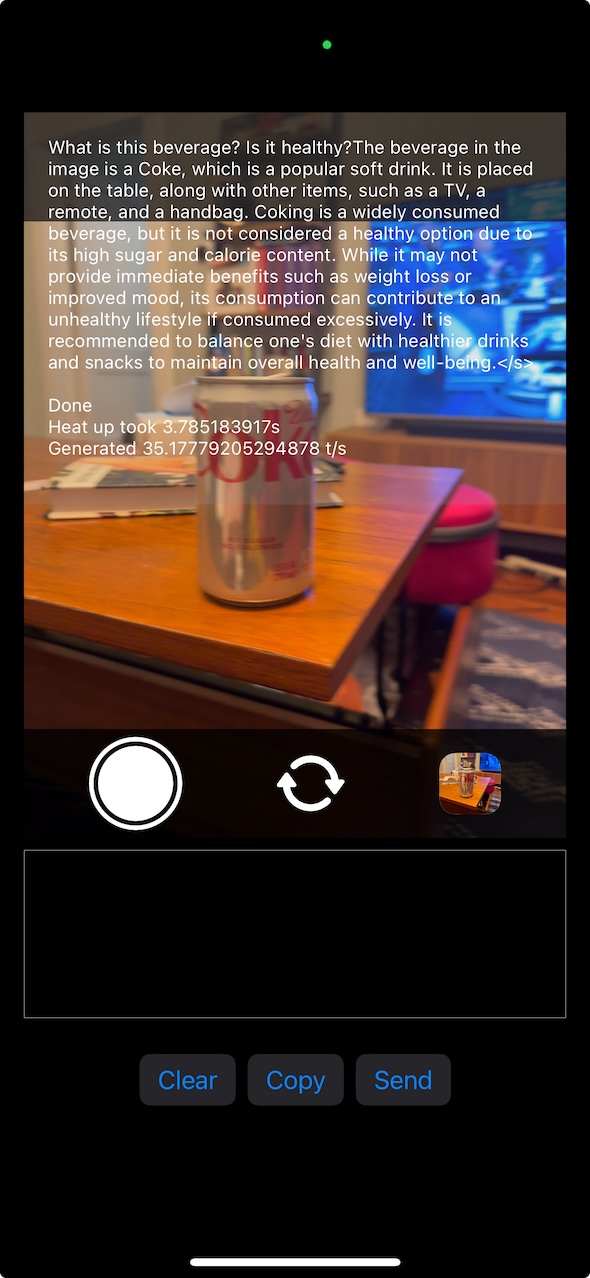

All that pain being said, it honestly “works” better than I expected! The UX, code, etc is a major mess and totally not cleaned up at all! But at this point, i’ve hacked on this off and on over 5+ months and I think it’s worth putting out there. Here’s an example query:

|

|

|---|---|

| The UI doesn’t separate prompt and answer, but it ends after the second question |

Some of the cool things it does, or that I learned:

- Inference is really fast, but loading the image takes some time, so it doesn’t quite feel as fast as it could be

- Running models on device I think is a really really interesting opportunity. For example, if you could run function calling on device, you can embed smarts into your app’s UX without needing internet. Imagine auto filling out an expense report immediately without needing to upload it. I think prompt engineering could go really far here.

- I learned a lesson about how important sampling logic is. Originally, I was re-using the manually rolled out sampling logic from llama.swiftui, but I didn’t handle using the different chat template that TinyLlama uses. It was very interesting to see the difference in how bad it was, and then implementing sampling correctly and seeing how good it was (relatively)

- The battery usage is surprisingly… okay? I haven’t actually measured it, but I will say that compared to the 7B model I tried, it’s way better than I expected.

- llama.cpp is awesome! the API is pretty great, and I learned a ton from integrating it into my project. I think it could very well be used

Conclusion

I don’t know if I will continue hacking on this specifically. I learned a lot, and I may incorporate it into some future project, but this was mainly a learning exercise that I kind of stumbled into. I had a vision of a “todo list” app that you never needed to type into. You could just “wear” a camera, and it would watch what you see/do, and add items to your todo list, with appropriate deadlines, automatically - you just need to follow the list! I still think that could be an interesting continuation here, but i’m interested in continuing my learning on both the training and implementation side - specifically I’m curious how to use coreml to run transformer / LLM models, and I really want to see how well function calling could work on device.

Appendix - How did training work?

I learned a ton training the model too, even if it was mostly done by running the scripts in the LLaVA repo (after pounding my head against my table for hours). To understand how training the smaller model worked, it helps to have a more detailed understanding of how LLaVA works.

CLIP + LLaMA = LLaVA

I’m not a deep learning or AI expert at all, so this explanation is almost certainly not accurate or precise, but here’s my best summary of how LLaVA training and inference works

Inference

I want to start with describing inference, as I think describing how inference works makes it easier to understand how training works.

Normally, text-only transformer based LLMs work by converting the input text into tokens, and then converting the tokens to embeddings. Then, the inference code will run the transformer algorithm to produce the output probabilities of each token in the vocab space, and it will select the token based on what strategy is selected.

LLaVA (and other vision + text models) take a fairly straightforward approach to extend how text-only LLMs work. The inference code accepts two types of inputs now – the image (or images) as well as the text of the query. Since an LLM model expects text embeddings as the input before running the transformer algorithm, LLaVA first needs to converts the input Image into text embeddings. It does this by converting the image to CLIP embeddings, and then running the clip embeddings through a linear layer which maps it into the text embedding space. From here, the inference code works just like the input were just text.

That’s it! I have to say, I appreciate the simplicity, and it makes some intuitive sense. CLIP was trained to produce the most relevant text snippet given an image, so it makes sense that you could translate those embeddings to the embeddings that the LLM understands.

Training

Now that we have a good idea about how inference works, it’s relatively simple to understand how LLaVA was trained. There are two steps to training LLaVA: pretrain and finetuning. Pretraining trains the projection layer that maps the CLIP embeddings to the model’s text embedding space. Finetuning then is training both the projection layer as well as the weights of the LLM. I’m not gonna go too deep here though, I recommend just reading the paper .

One important thing is that LLaVA is not an LLM trained from scratch. The LLM weights come from a base model. The initial version of LLaVA was trained with Vicuna used as a starting base, and the smallest available Vicuna model is 7B parameters, and that was the smallest model that the LLaVA authors had trained at the time of the release.

Making LLaVA smaller

Knowing LLaVA was trained, it should be fairly obvious how to make LLaVA smaller - just use a smaller base model!

Thankfully the LLaVA authors have described how to download the training data they used, as well as have the scripts written to train the model. I chose TinyLlama-Chat (which has 1.1B parameters) mainly because when I ran llama.swift (the iOS example in llama.cpp) on my phone, it actually ran fairly quickly with no crashes, so I knew that it should run on my phone after being trained.

Here’s the model weights, and the projection layer weights. I have not run the llava eval scripts to see how good it actually is, but in my testing, it worked fairly well.

Training woes

While I was extremely grateful to have a script that essentially automated all the training I needed to do, I ran into many hiccups, draining my motivation for months at a time.

Why did I get this M3 Max?

Late in 2023, I purchased a fully decked out M3 Max, with the idea that, there’s not going to be an easy way to access 128GB of memory that could be used for deep learning. Naively, I thought that the ecosystem was gradually going to become more and more compatible with M-series macs quickly. I modified the scripts a bit to run on my macbook, and I figured it would be slower. While I was able to get the training loop to “run”, I had to disable the 8bit optimizer, and the training loss graphs just never looked right. I spent way too long trying to get it to work before giving up and just using RunPod. I can’t wait for the day bitsnbytes is compatible with M-series macs.

Shuffling training data

The training data was 100s of gigabytes. It’s annoying to pay for GPU time when it’s just sitting around waiting for the data needed to train to download. One of the scripts to download the data did not parallelize downloads, so I modified it to do some asyncio python downloads.

Training script updates

The training scripts were written in such away that to handle retraining with different base models which was super helpful! But TinyLlama-Chat uses a conversation format that wasn’t supported by default, and it was fairly difficult to verify that the conversation template was used in all the places it needed to be.

Training Conclusions

I don’t have a lot to synthesize here, but my takeaways in no particular order:

- NVIDIA is king, M-series Macs for deep learning is very niche and unless the model you’re interested is specifically targeting deployment on Apple hardware, it will be very hard to recreate a project’s results.

- training is hard even if you have scripts written for you. expect to need to read most lines of code to make even minor changes to setups.

- RunPod is fantastic - I don’t get any revenue from them I just want to praise them for lots of availability, easy to get started.

- Small models train faster than you think

- A huge shoutout to all models that actually publish their datasets and provide scripts to integrate them to reproduce models!

[^1] Sure, you could just use ChatGPT’s exceptional mobile app, but that’s not very fun.